How Preventive Maintenance Extends the Life of Your Lab Equipment

Introduction

Unexpected breakdowns don't just pause your experiments, they waste money, slow down projects, and stress your team. The best way to prevent this is to treat your lab equipment like an important investment. A good preventive maintenance (PM) plan helps your instruments run safely, give accurate results, and last many years longer than if you just use them until they fail. In this article, you'll learn how simple steps like regular checks, calibrations, and basic cleaning can greatly extend the life of your lab equipment and how a well-planned maintenance routine can quickly pay for itself.

What Is Preventive Maintenance?

Preventive maintenance means taking care of lab instruments before they break down. Instead of waiting for a freezer to stop cooling or an incubator to go out of range, the lab follows a planned schedule of checks and servicing. This usually includes cleaning, lubrication, calibration, software checks, and changing parts that wear out over time, like filters, gaskets, belts, bulbs, and seals. How often this is done depends on the manufacturer's advice, how much the equipment is used, and how important it is for the lab's work. In a well-managed lab, every key instrument such as biosafety cabinets , incubators , freezers , centrifuges, shakers, and analytical systems has its own maintenance plan. Simple daily or weekly tasks are done by lab staff, while deeper servicing is done every few months or once a year by trained service engineers. Everything is written down in a maintenance log so the lab can show auditors what was done and decide when to repair, upgrade, or replace a unit.

The main purpose of preventive maintenance is to reduce sudden breakdowns, protect valuable samples, and keep data quality high. Equipment that is properly maintained is less likely to fail in the middle of an important experiment and more likely to stay within its set limits, giving steady and reliable results. At the same time, looking after instruments reduces wear and heat stress, helps them last longer, and delays the need for costly replacements. This makes it easier to plan budgets and avoid surprise costs. In this way, preventive maintenance is not just "routine service", it is an important part of quality control, risk management, and long-term cost saving in the laboratory.

Why Lab Equipment Dies Early (Even When It's 'New')

It's frustrating when a "new" incubator, centrifuge , or freezer starts giving trouble long before you expected. On paper, the instrument may only be a few years old, but in reality it might already have lived a very hard life. Early failure usually isn't about bad luck,it's about how the equipment is installed, used, and cared for from day one.

Many instruments are pushed straight into heavy workload with no proper commissioning. They are often pushed into small spaces with poor ventilation, near heat sources, under direct sunlight, or right beside vibrating equipment. Compressors, fans and electronics then run hotter than they should, every single day. Over time, that extra heat quietly destroys components long before their actual design life.

Another silent killer is "invisible misuse". Doors are left open too long, rotors are overloaded just this once, samples are unbalanced, or the wrong racks, tubes or accessories are used. The instrument still runs, so the team assumes everything is fine, but inside, bearings, seals, motors and sensors are being stressed. A freezer that is constantly opened and stuffed beyond its rated capacity, or a centrifuge that's routinely run with slight imbalance, will almost always die early even if it's technically new.

Dirty environments and poor housekeeping also shorten life dramatically. Dust-clogged vents, unclean chambers, spilled media, and unwashed filters force motors and compressors to work harder to deliver the same performance. A blocked condenser on a freezer or a CO₂ Incubator that's never properly cleaned can easily lead to overheating, unstable conditions and premature failure.

Poor Lab Maintenance

On top of this, many labs run equipment with little or no calibration or diagnostics. Small problems like temperature drift, strange noises, slow ramp times, intermittent alarms are ignored until one day the instrument finally fails during a critical run. By then, the damage is usually expensive and sometimes irreparable, even though a simple preventive maintenance visit months earlier could have caught the issue.

In short, lab equipment doesn't die early because it's new; it dies early because it's treated as if it will run forever without care. The good news is that this is completely fixable. With correct installation, user training, basic daily checks, and a structured preventive maintenance plan, you can turn those same instruments into long-lived, reliable workhorses instead of costly surprises

How Preventive Maintenance Helps (The Simple Benefits)

Preventive maintenance is about treating your lab equipment as an important long-term investment. By planning regular cleaning, calibration, inspections, and timely replacement of wear parts, you stop small problems from turning into major faults. A loose incubator door, a centrifuge that sounds slightly off, or a dusty freezer condenser might seem minor today, but over time they put extra load on motors, compressors, and electronics. Preventive maintenance helps you spot these issues early, tighten and adjust components, clean critical areas, replace worn parts, and keep the equipment running under minimal stress. As a result, you see far fewer sudden breakdowns and less last-minute searching for spare instruments.

This regular care also has a big effect on the quality of your test results, your budget, and your compliance. Instruments that slowly move out of calibration often still look like they are working normally, but they can quietly produce wrong readings, cause failed runs, and waste reagents, samples, and staff time. By doing routine checks and calibrations, you keep important parameters like temperature, speed, airflow, pressure, and optical performance within the correct limits set by the manufacturer or your method. This leads to more stable and repeatable experiments, fewer rejected batches, and more trust that unusual results are real and not caused by faulty equipment. In everyday lab life, this means smoother workflows, less downtime, and fewer arguments about whether an instrument is to blame. Financially, planned maintenance is easier to budget and normally cheaper than emergency repairs or buying a new unit at short notice. Extending the life of costly equipment like freezers, incubators, biosafety cabinets , and analyzers by even a few extra years can save a lot of money. At the same time, keeping proper service records and proof of maintenance makes audits and inspections much easier, because you can show that your lab is safe, controlled, and follows regulations. What first looks like extra work actually reduces stress: fewer surprises, fewer repeat tests, fewer conflicts, and equipment you can rely on when your results are critical.

Well-Organized Modern Laboratory

Easy Habits You Can Start This Week

You don't need to completely redesign your maintenance system to see real benefits. A few small, consistent routines are enough to extend the life of your incubators, freezers, centrifuges , autoclaves and safety cabinets. Think of it as giving each key instrument a bit of daily attention instead of waiting until it fails. A quick look-over at the beginning of the day, a brief wipe-down before leaving, and a simple log sheet on the door already help prevent surprises, make problems easier to catch early, and provide clear documentation for audits or service visits.

Lab Technicians Updating Equipment Maintenance Checklists And Records.

Once these small habits are built into the normal workflow, the lab environment becomes noticeably calmer: fewer urgent breakdowns, fewer disagreements about who damaged what, and greater confidence in the equipment.

Below is a simple way to structure those habits so your team can actually use them this week:

Task Check | What you do | How often | Why it helps |

30-second check | Look at the display, listen for unusual noise or vibration, and confirm temperature/speed/CO₂ is normal before using the instrument. | At the start of each shift or before the first run. | Catches early warning signs before they become failures and prevents starting critical runs on a sick instrument. |

Quick wipe-down | Clean doors, handles of instruments , control panel and any visible spills inside/outside the unit using appropriate wipes or disinfectant. | At the end of the day. | Reduces corrosion, contamination and sticky parts that strain hinges, seals and sensors. |

Logbook on the door | Record date, initials, basic status on a sheet or clipboard fixed to or beside the equipment. | Every time the instrument is used or checked. | Creates instant documentation for audits and gives engineers a clear history when troubleshooting. |

Dust & door check | Wipe dust from vents and grills, inspect door gaskets for cracks or deformation, and confirm doors close smoothly and seal properly. | Once a week. | Protects compressors, fans and heaters from overheating and stops cold/heat loss that shortens equipment life. |

Next service sticker | Place a bright label with Next PM due: [month/year] where everyone can see it, and update after each service. | Updated after each professional service visit. | Keeps preventive maintenance on the radar so scheduled service is less likely to be forgotten or delayed. |

You can start with just one or two of these and build up, but the important part is consistency-small, repeatable habits that quietly keep your equipment ready for the moments that really matter.

Simple Example by Equipment Type

It's easier to get people to care about maintenance when they can picture it on the exact equipment they use every day. Instead of talking about assets and programs, imagine that one centrifuge everyone fights over, the CO₂ Incubator full of precious cells, or the freezer packed with years of samples. A tiny habit with each of these things that takes less than a minute, can be the difference between a normal day and a disaster with melted samples or shattered rotors. The examples are designed so that even a busy scientist or technician can look at them and think, "This is doable right now."

Equipment Type | Simple Habit This Week | What You're Quietly Preventing | How It Shows Up in Real Life |

Centrifuge

| Before the first spin of the day, open the lid, really look at the rotor, wipe any old spills, and make sure tubes are properly balanced. | Hidden rotor cracks, extra vibration, damage to the motor and lid lock that leads to sudden, expensive failure. | The centrifuge sounds smoother, runs feel less scary, and you stop worrying that today is the day it will fail with your best samples inside. |

CO₂ Incubator / Incubator

| When you load or unload, glance at the door gasket, check temperature and CO₂ against your log, and notice any odd smell or condensation. | Slow temperature and CO₂ drift, contamination building up in corners, and leaky doors that force the system to overwork. | Cells grow more predictably, mystery contamination becomes rare, and the incubator stops being the villain everyone blames. |

Laboratory Freezer / Refrigerator

| Once this week, open the door, look at the seal, knock back obvious ice, and clean dust from the front grill or condenser area if accessible. | Overheated compressors, struggling fans, thick ice that ruins door seals, and those painful temperature excursions. | The temperature stays steady, no more midnight alarms, and you don't have to rush to rearrange everything in the freezer. |

| Before starting work, confirm airflow and alarm status, check the front and rear grills aren't blocked, and finish by wiping the work surface properly. | Poor containment, airflow problems, and unsafe work conditions that risk both staff and experiments. | You feel genuinely safer at the bench, plates stay cleaner, and airflow alarms become rare instead of just another sound in the lab. |

Shaker / Vortex Mixer

| Take a moment to check that clamps, platforms or heads are tight, the cord is healthy, and run it briefly at low speed just to listen. | Loose loads flying off, stressed motors, and sudden mechanical failure right in the middle of an overnight shake. | Flasks stay where you put them, the shaker no longer walks across the bench, and people trust it enough to leave it running. |

Water Bath / Heating Block

| Look at the water level or block surface, remove any debris, and occasionally verify the displayed temperature with a simple reference thermometer. | Burned-out heaters, limescale buildup, and quiet temperature drift that ruins incubations without obvious alarms. | Incubations finish on time with the results you expect, and you don't waste reagents repeating runs because the bath might have been off. |

Preventive maintenance stops feeling like extra work and starts looking like self-defense for your experiments: tiny, realistic actions on familiar equipment that protect your samples, your schedule, and your sanity.

Common Mistakes That Shorten Equipment Lifespan

Most labs don't destroy equipment with one big mistake; they wear it down with lots of small, normal habits. These feel harmless on a busy day, but together they shorten instrument life, damage samples, and blow up your maintenance budget. Here's a sharper look at the patterns that do the most damage and how to break them.

Common Mistake | What Really Happens Behind the Scenes | Simple Way to Fix It |

Treating maintenance as optional admin | Equipment runs until something fails in the middle of a critical run, turning a cheap fix into an emergency repair or replacement. | Put a due-date sticker on every key instrument and treat it like an expiry date you don't ignore. |

Silencing alarms instead of investigating them | Normal alarms hide real problems; by the time someone takes it seriously, parts are already overheated, worn out, or off-spec. | Every recurring alarm gets logged once and checked once with no exceptions. |

Overloading, cramming, and just this once use | Overpacked freezers, unbalanced centrifuges, and overloaded shakers stress motors, rotors, seals and hinges far beyond design limits. | Respect the capacity label; if you're always overfull, the problem is capacity, not the instrument. |

Running dirty equipment (dust, ice, spills) | Dusty vents, iced-up coils, sticky chambers and dirty sensors force systems to work harder and run hotter, killing them early. | Make clean, clear vents and chambers a weekly visual standard, not a once-a-year deep clean. |

No shared maintenance log | Issues live in people's heads; patterns are missed; engineers and auditors see only fragments and can't help you prevent repeats. | Keep a one-page log on or near the instrument so anyone can see its story at a glance. |

Buying parts only after a failure | You wait days or weeks for critical spares, while samples, schedules and staff time sit on hold. | Keep a small first-aid kit of common parts (filters, gaskets, bulbs, O-rings) for your most critical units. |

When you show your team these mistakes in plain language, they instantly recognize them from everyday life in the lab. Fixing even one or two of them is often enough to turn your equipment from fragile and unpredictable into a reliable backbone your whole lab can trust.

Disorganized Laboratory Desk

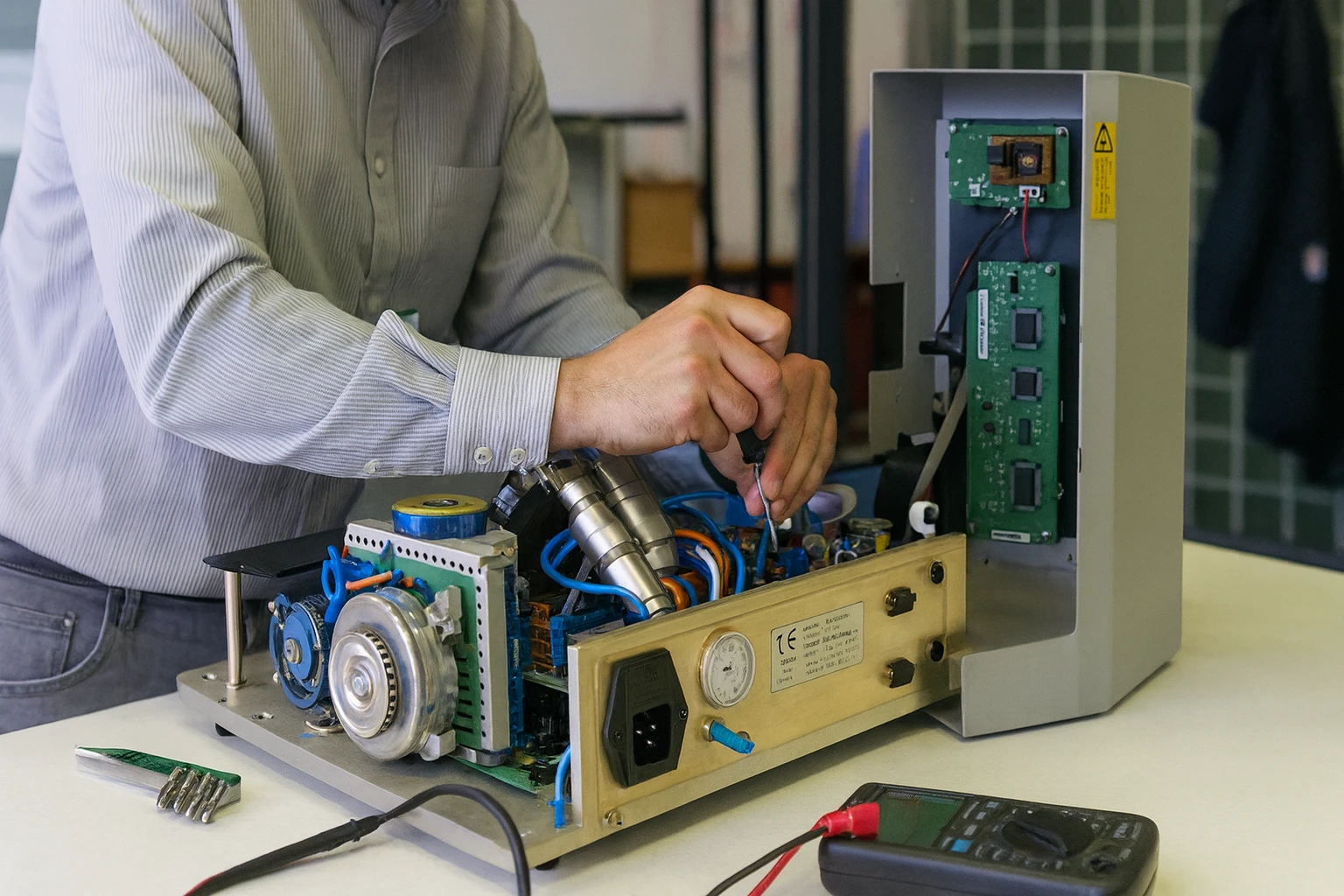

When to Call a Service Engineer

A simple rule for the lab is this: if a problem keeps coming back or starts affecting your results, it's time to call a service engineer. One-time glitches can happen, but if the same alarm, strange noise, temperature drift, or error message appears more than once, the instrument is warning you that something is wrong. For example, an incubator that takes longer than usual to reach temperature, a freezer that slowly creeps above its setpoint, or a centrifuge that shakes even with a balanced load are all early warning signs. You might be able to work around them for a short time, but every extra day puts more stress on the equipment and increases the chance of a sudden, costly failure in the middle of important work.

You should also call a service engineer right away if there is any safety risk or loss of control. This includes burning smells, visible sparks, damaged power cords, door locks that don't close properly on centrifuges or incubators, biosafety cabinets with alarms that won't clear, or any situation where the instrument can't reliably hold its temperature, speed, pressure, or airflow. In these cases, switch the unit off and mark it "OUT OF SERVICE" until it's checked. It's also smart to bring in a professional at key moments: before a major study, before an external audit, after the equipment is moved, or when a unit is close to the end of its warranty. A planned service visit at these times is much cheaper than losing samples or failing a validation later. In short, don't wait for a total breakdown, use your logs, alarms, and common sense, and involve a service engineer as soon as equipment starts acting "not quite right" and basic cleaning or user checks don't solve it.

Service Engineer Fixing Instrument

The Bottom Line for Your Lab

When you look after your equipment before it fails, you're not just being careful, you're actively protecting your samples, your schedule, your team, and your budget. A simple routine of daily checks, basic cleaning, clear maintenance logs, and timely visits from a service engineer can turn incubators, freezers, biosafety cabinets, centrifuges and other instruments from constant worries into dependable tools you barely have to think about. That shift from "fix it when it breaks" to "protect it before it fails" is exactly where you gain real savings, stronger safety, and cleaner, more reliable data.

If you're ready to move away from stress, surprises and last-minute repairs, now is the time to act. Pick your most critical equipment, agree on a few easy daily and weekly checks, and set up a preventive maintenance plan. To get started or to design a maintenance program tailored to your lab, contact us through our website and our team will help you build a simple, effective preventive maintenance schedule for your instruments.The best time to protect your equipment was when you bought it. The second-best time is today